Low- to Mid-Fee Schools

Business Model Description

Establish or acquire and operate independent and cost-effective private school chains on the primary and secondary level targeting the growing middle class in the urban centres at a low- to mid-fee price level. The schools either run as commercial entities where a private actor owns and operates the entity or via a public-private partnerships where the entity is government-owned but managed and operated by the private sector. For the latter case, the government provides the necessary infrastructure, such as repurposing abandoned and / or underutilized buildings and renting them to users.

Expected Impact

Improve access, equity and quality in primary and secondary education especially for low- to middle-income households in urban centers.

How is this information gathered?

Investment opportunities with potential to contribute to sustainable development are based on country-level SDG Investor Maps.

Disclaimer

UNDP, the Private Finance for the SDGs, and their affiliates (collectively “UNDP”) do not seek or solicit investment for programmes, projects, or opportunities described on this site (collectively “Programmes”) or any other Programmes, and nothing on this page should constitute a solicitation for investment. The actors listed on this site are not partners of UNDP, and their inclusion should not be construed as an endorsement or recommendation by UNDP for any relationship or investment.

The descriptions on this page are provided for informational purposes only. Only companies and enterprises that appear under the case study tab have been validated and vetted through UNDP programmes such as the Growth Stage Impact Ventures (GSIV), Business Call to Action (BCtA), or through other UN agencies. Even then, under no circumstances should their appearance on this website be construed as an endorsement for any relationship or investment. UNDP assumes no liability for investment losses directly or indirectly resulting from recommendations made, implied, or inferred by its research. Likewise, UNDP assumes no claim to investment gains directly or indirectly resulting from trading profits, investment management, or advisory fees obtained by following investment recommendations made, implied, or inferred by its research.

Investment involves risk, and all investments should be made with the supervision of a professional investment manager or advisor. The materials on the website are not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any investment, security, or commodity, nor shall any security be offered or sold to any person, in any jurisdiction in which such offer would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction.

Country & Regions

- Tanzania: Central Zone

- Tanzania: Eastern Zone

- Tanzania: Western Zone

Sector Classification

Education

Development need

Significant progress has been made in expanding free primary education in Tanzania, raising primary and secondary enrolment rates and increasing investment in higher education. However, Tanzania’s Human Capital Index (HCI) remains well below the average of low and low middle income countries. Access to education is highly unequal, and a lack of qualified teachers undermines learning outcomes (1).

Policy priority

Tanzania's government is committed to develop and maintain a skilled and competitive workforce through increasing enrolment of age-appropriate children; construction of classrooms and teacher allocation to keep pace with the rapid increase, and the incorporation of digital learning and teaching (2, 8, 21).

Gender inequalities and marginalization issues

The ratio in primary and lower secondary schools for girls to boys is about 1:1, while in upper secondary and higher education it is 1:2. This shows a decreasing trend for the progression of girls from one level to the other. Although drop out affects both boys and girls, girls have a greater possibility for leaving school prematurely (3).

Investment opportunities introduction

Tanzania has one of the world’s fastest growing young people’s population. Of the estimated 60 million people, more than 50% are under 18 and over 70% are under 30. Tanzania requires means of educating these large numbers of young people, which offers engagement opportunities (6, 7).

Key bottlenecks introduction

Despite important gains in primary enrolment, learning outcomes remain broadly unchanged. The distribution of educational opportunities is highly unequal, and a lack of qualified teachers undermines education quality (5).

Formal Education

Development need

Tanzania made primary education free in 2002, and has since nearly achieved universal primary education. The shift now is into secondary education. Tanzania still faces some issues, such as the shortage of teachers and classrooms, as well as inequality in access to educational services (1, 4, 12).

Policy priority

Tanzania has put in place policies to promote diversity of supply for independent private schools. Individuals, private organizations, and non-government organizations are legally permitted to own and operate private schools. These can be community, not-for-profit, faith based or for-profit providers (4).

Investment opportunities introduction

The expanding middle class, representing 10% of the population and growing at a steady rate, offers significant demand for quality education in line with international standards, life skill development, education infrastructure and learning tools, including digital technology and education IT solutions (8, 35).

Key bottlenecks introduction

Significant progress has been made in expanding free primary education, raising primary and secondary enrolment rates, and increasing investment in higher education. However, Tanzania’s Human Capital Index (HCI) remains well below the comparable average. Access to education is highly unequal, and a lack of qualified teachers undermines learning outcomes (1).

Pipeline Opportunity

Low- to Mid-Fee Schools

Establish or acquire and operate independent and cost-effective private school chains on the primary and secondary level targeting the growing middle class in the urban centres at a low- to mid-fee price level. The schools either run as commercial entities where a private actor owns and operates the entity or via a public-private partnerships where the entity is government-owned but managed and operated by the private sector. For the latter case, the government provides the necessary infrastructure, such as repurposing abandoned and / or underutilized buildings and renting them to users.

Business Case

Market Size and Environment

< USD 50 million

8,799,341 students seeking to transition from primary to secondary schools and cannot be catered by from the government budget

Average government spending for free education in Tanzania is USD 59 million per year. Private schools comprise of only 2% and 18% of the primary and secondary school students, respectively (10,11,12).

The number of primary and secondary school students is estimated at around 10,601,616 and 2,338,457, respectively. The transition rate from primary to secondary level is 17%, which means that currently 8,799,341 students are left out (19, 31).

Indicative Return

> 25%

Experience from investors in “low- to mid-fee private schooling” in South Africa shows that profit margins of 30-40% are achievable for monthly fees above ZAR 3,000 (USD 189). For medium-fee (below ZAR 3,000 (USD 189) per month) schools, returns of up to 30% are common (34).

A cost-benefit analysis of the education expenditures using the human capital approach shows that education enrolments have positive net-benefits with a benefit-cost ratio of 1.3-2.9 irrespective of the timing of the benefits and costs, and the discount rate alternatives considered (15).

The returns on investments for a year of schooling by world region are highest in Sub-Saharan Africa, standing at 12.4%, which is significantly above the global average of 9.7%. Returns for Tanzania are estimated at 19.2%, which are among the highest within Sub-Saharan Africa (13, 16).

Investment Timeframe

Medium Term (5–10 years)

Based on South African benchmarks, private school investments are likely to produce a cash-flow in the short to medium term depending on the quality and the speed of the marketing process to attract pupils (34).

Ticket Size

< USD 500,000

Market Risks & Scale Obstacles

Market - Volatile

Business - Supply Chain Constraints

Impact Case

Sustainable Development Need

Tanzania's free basic education system has resulted in primary education gross enrolment rates becoming universal, at 96.9%, with net enrolment standing at 84% and more than 70% of the primary school leavers transiting to secondary education. This has put pressure on the country’s public education system (21).

The population structure in Tanzania places a premium on the cost of education and other social services. By 2025, the system will have to cater for further 6.3 million pupils of which 4.7 million will be enrolled in basic education. There are increasing concerns about the quality of education and learning outcomes especially at basic education levels (21).

Gender & Marginalisation

Nearly 61% of female youth of secondary school age are out of school compared to 51% of male youth of the same age. The biggest disparity can be seen between low- and high-income households (17).

Expected Development Outcome

Low- to mid-fee schools present a cost-effective option for improving access and equity in education. Private schools can fill a supply gap given that there is demand to expand faster than public infrastructure can support (11).

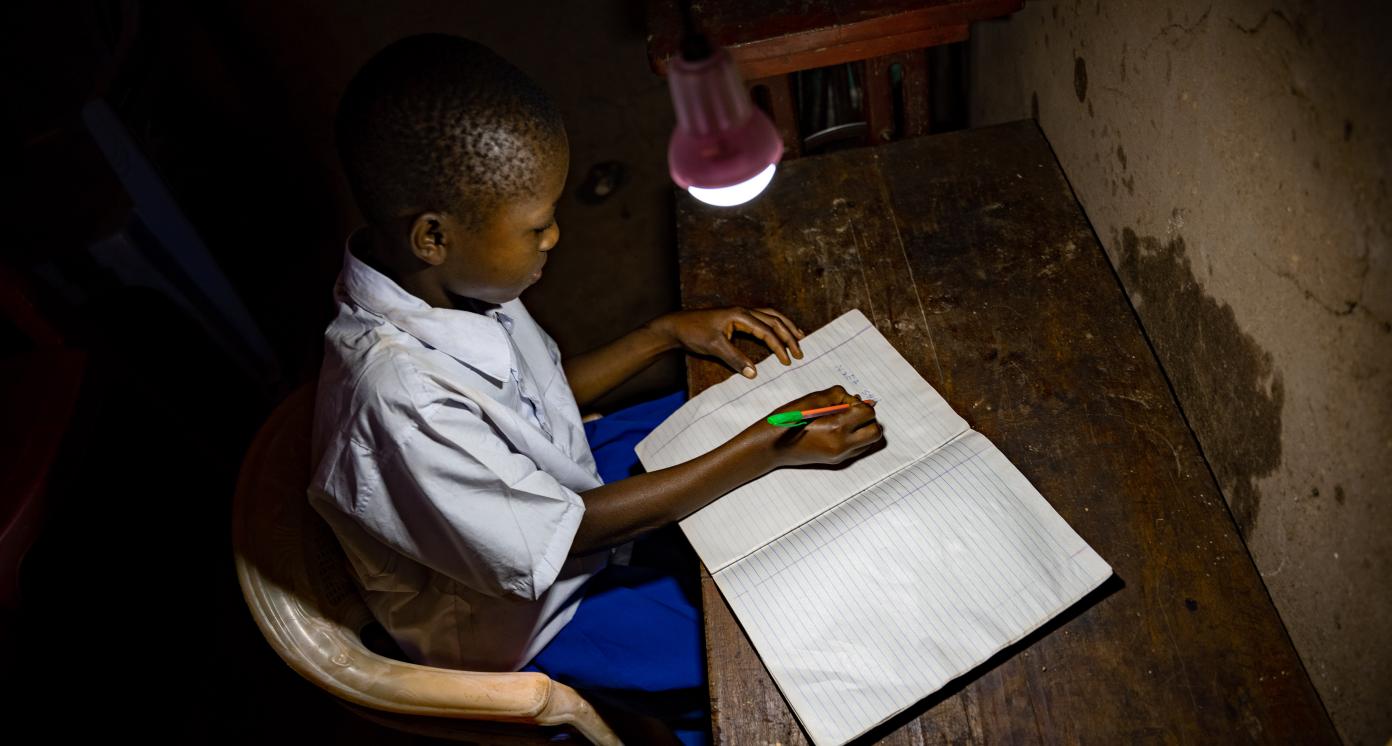

Enhanced schooling increases the scope for youth to benefit from the transition underway in the economy and more specifically get skills demanded by the emerging sectors of the economy. Research has shown that those with post-secondary or university education earn approximately 40 times more than those without education, while completing primary education yields about four times the earnings of those with no schooling (35, 36).

Gender & Marginalisation

Low- to mid-fee schools offer female students, particularly from middle income families, basic knowledge and skills, which prepares them to provide services needed in the competitive job market and in return receive higher incomes to improve their livelihoods (11, 35, 36).

Primary SDGs addressed

4.1.2 Completion rate (primary education, lower secondary education, upper secondary education)

4.6.1 Proportion of population in a given age group achieving at least a fixed level of proficiency in functional (a) literacy and (b) numeracy skills, by sex

4.a.1 Proportion of schools offering basic services, by type of service

4.5.1 Parity indices (female/male, rural/urban, bottom/top wealth quintile and others such as disability status, indigenous peoples and conflict-affected, as data become available) for all education indicators on this list that can be disaggregated

Transition rate of 77.5% from standard 7 to form 1 and percentage of transition rate of 19.2% from form 4 to form 5 in 2020/21 (8).

Adult literacy rate estimated at 77.6% in 2020/21. Improve examination pass rate in mathematics estimated at 20% in 2020/21 (8).

The proportion of primary schools with access to electricity was 69.8 % in 2020/21. Proportion of schools with clean water estimated at 68.5% in 2020/21 (8).

The gender parity index for participation rate in organized learning (one year before the official primary entry age) increased from 1.0 in 2004 to 1.1 in 2018 (39).

Transition rate of 95.9% from standard 7 to form 1 and percentage of transition rate of 23% from form 4 to form 5 in 2025/26 (8).

Adult literacy rate estimated at 81.6% in 2025/26. Improve examination pass rate in mathematics estimated at 25% in 2025/26 (8).

The proportion of primary schools with access to electricity is projected at 85 % in 2025/26 (8). Proportion of schools with clean water projected at 88.5% in 2025/26 (8).

N/A

8.6.1 Proportion of youth (aged 15–24 years) not in education, employment or training

Estimated at 14.9% (39).

N/A

Secondary SDGs addressed

Directly impacted stakeholders

People

Gender inequality and/or marginalization

Corporates

Public sector

Indirectly impacted stakeholders

People

Corporates

Outcome Risks

If the private schools target primarily higher performing students and / or focus on students from higher-income households, leaving disadvantaged youths in the public system, they may exacerbate existing inequalities and draw away public education funds (11).

A limited pool of qualified teaching staff locally may necessitate outsourcing, which may increase operation costs and result in unaffordable service provision (11).

Impact Risks

If the private schools are inaccessible and unaffordable to students from low-income communities, only those already served by public schools may benefit and the expected impact may be limited.

Uncoordinated efforts in curriculum development may influence teachers’ reliance on the follow-repeat-and-memorize-methods, rather than problem-solving, which may obstruct the quality of learning and limit the expected impact (21).

A limited pool of qualified teaching staff locally may necessitate outsourcing, which may limit the resultant job opportunities for Tanzanians and reduce the expected impact.

Impact Classification

What

Low- to mid-fee schools improve access, equity and quality in primary and secondary education.

Who

Low- to middle-income households in urban centers obtain schooling options, and the education workforce gets access to job opportunities through low- to mid-fee schools.

Risk

While the low- to mid-fee schools model is proven, affordability for low-income communities, quality of service provision and availability of qualified teaching staff require consideration.

Impact Thesis

Improve access, equity and quality in primary and secondary education especially for low- to middle-income households in urban centers.

Enabling Environment

Policy Environment

Education and Training Policy (ETP), 2014: Provides statements that direct the transition to fee-free and compulsory basic education of 11 years, including one year of mandatory pre-primary education (18).

Education Sector Development Plan, 2016/17-2020/21: Presents Tanzania’s commitment to providing 12 years of free and compulsory basic education. Outlines the overall strategy for transforming the sector into an efficient, effective and outcome-based system (19, 21).

Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Policy for Basic Education, 2007: Focuses on integrating of ICTs in pre-primary, primary, secondary and teacher education, as well as non-formal and adult education (20).

Education Policy, 1978: Describes the role of the private sector in primary and secondary education. It sets out a 14-point criteria upon which a school can be granted or denied registration (36, 37).

Financial Environment

Financial incentives: The Global Partnership for Education (GPE) offers grants totalling USD 112 million to build on Tanzania’s efforts to get more children in school. Investors can benefit from a special package for girls and children from disadvantaged backgrounds (25).

Fiscal incentives: Tanzania offers import duty and VAT exemption on deemed capital goods, including building materials, utility vehicles and equipment. Private schools are among the potential beneficiaries of the scheme (26).

Regulatory Environment

National Education Act, 2019: Guarantees compulsory primary education for every child who has reached the age of seven years. It stipulates that no child shall be refused enrolment in school and parents shall ensure that the child regularly attends primary school (22).

Education Act, 1978: Allows private sector to operate schools in Tanzania, and affords private schools’ moderate levels of autonomy. They can set teacher salaries, deploy and dismiss teachers (subject only to labor laws) and they have to adhere to centralized requirements on teacher qualifications, class sizes and pedagogy (23, 37).

Education Act 10, 1995: In order to operate, independent private schools are required to pay an inspection fee of USD 3 per student per year, as well as an examination fee of USD 9 for each student in a grade where standardized examinations are administered (24, 37).

Marketplace Participants

Private Sector

Silverleaf Academy, FEZA Boys, Dar es Salaam Independent School, St Francis Secondary Schools, Aga Khan Schools, Dar es Salaam International Academy, St. Augustine Secondary School.

Government

Ministry of Education, Higher Education Accreditation Council, President's Office Regional Administration and Local Government (PO-RALG), Tanzania Institute of Education, Agency for Development of Educational Management, Commission for Science and Technology (COSTEC).

Multilaterals

World Bank Group (WBG), United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Non-Profit

HakiElimu, East Africa Youth Inclusion Project (EAYIP), TWAWEZA, Tanzania Education Network / Mtandao wa Elimu Tanzania (TENMET), Tanzania Food For Education (TAFFED), CAMFED Tanzania, Born to Learn (BTL).

Public-Private Partnership

Higher Education Students’ Loans Board (HESLB) with the objective of assisting needy and eligible Tanzania students to access loans and grants for higher education.

Target Locations

Tanzania: Central Zone

Tanzania: Eastern Zone

Tanzania: Western Zone

References

- (1) World Bank, 2021. Tanzania Economic Update. Raising the Bar for Achieving Tanzania’s Development Vision.

- (2) United Republic of Tanzania, 2016. National Skills Development Strategy 2016/17 – 2025/26.

- (3) United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2016. Empowering Adolescent Girls and Young Women through Education in Tanzania.

- (4) United Republic of Tanzania, 2015. Engaging the Private Sector in Education, SABER Country Report.

- (5) The World Bank, 2021. Tanzania Economic Update.

- (6) The British Council, 2016. Tanzania’s Next Generation Youth Voices.

- (7) United Nations Children's Fund, 2018. Young People Engagement: A priority for Tanzania.

- (8) United Republic of Tanzania, 2021. Third National Five-Year Plan (FYDP 3).

- (9) Silverleaf Academy, 2022. http://www.silverleaf.co.tz.

- (10) East African Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 2020. Challenges on the Implementation of Free Education Policy in Tanzania: A Case of Public Primary Schools in Babati Town.

- (11) World Bank Group, 2020. Low-Cost Private Schools in Tanzania. A Descriptive Analysis.

- (12) United Nations Children's Fund, 2020. Education Budget Brief, Mainland Tanzania.

- (13) World Bank Group, 2014. Comparable Estimates of Returns to Schooling Around the World.

- (14) FEZA Schools, 2022. https://fezaschools.org.

- (15) R, J Brent, 2009. A cost-benefit analysis of female primary education as a means of reducing HIV/AIDS in Tanzania. https://www.tandfonline.com.

- (16) World Bank, 2016. Trends in returns to schooling: why governments should invest more in people’s skills.

- (17) Family Health International, 2018. National Education Profile Update. https://www.fhi360.org/projects/strengthening-national-education-system.

- (18) United Republic of Tanzania, 2014. The Education and Training Policy.

- (19) United Republic of Tanzania, 2008. Education Sector Development Plan (ESDP).

- (20) United Republic of Tanzania, 2007. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Policy for Basic Education.

- (21) United Republic of Tanzania, 2016. Education Sector Development Plan, 2016/17-2020/21.

- (22) United Republic of Tanzania, 2019. National Education Act, Chapter 353, Principal Legislation.

- (23) United Republic of Tanzania, 1978. The National Education Act, 1978 (No. 25).

- (24) United Republic of Tanzania, 1995. Education Act No. 10.

- (25) Global Partnership for Education, 2020.

- (26) United Republic of Tanzania, 2022. Standard Incentives for Investors. https://investment-guide.eac.in.

- (27) Sustainable Development Goals Centre for Africa, 2020. Africa SDG Index and Dashboards Report.

- (28) The Borgen Project, 2018. Everything to Know About Tanzania’s Improving Economy.

- (29) World Bank, 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.PRM.ENRR?locations=TZ.

- (30) Feza Schools, 2022. https://fezaschools.org/achievements.

- (31) United Republic of Tanzania, 2018. Education Sector Performance Report.

- (32) Africa Aid, 2022. https://africaid.org/tanzanias-school-system-an-overview.

- (33) The World Bank Group, 2015. Service Delivery Indicators for Tanzania, Education and Health.

- (34) SparkSchools, 2020. South Africa, Tuition & Fees.

- (35) Africa Portal, Tanzania, 2015. Skills and Youth Employment. A Scoping Paper.

- (36) United Republic of Tanzania, 1978. Education Act.

- (37) Research on Improving Systems of Education, 2020. Low-Cost Private Schools in Tanzania: A Descriptive Analysis.